Eccentric Musings (jakaEM)

"I have undergone sharp discipline which has taught me wisdom; and then, I have read more than you would fancy." Emily Brontë

still figuring this place out - Jen W

Currently reading

Reading progress update: I've read 115 out of 288 pages.

True story: When Alice Munro won the Nobel, my very first thought was - "Alice? Not Margaret? Hmmm."

My second thought, on walking to my bookshelves was - "Holy crap. I have eight of her books sitting right here." Eight! Right at my finger tips! All of them forgotten and passed over as I looked for more 'interesting' fare ... usually of the Atwood variety (for they sit, side-by-side, on the shelves: literary comrades in so many ways); sometimes for something similar, albeit a little more peripheral (when Marian Engel got the nod).

Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Marian Engel ... Margaret Laurence and Carol Shields, too. All contemporaries in time and [roughly] place. All inextricably linked in my own head, and on my bookshelves. Waiting. Quiet and patient; wise and rich.

Oh My Antonia!

lord love a duck, I just spent 20 mins trying to find the right edition of My Antonia to add to my currently reading list here and at GR.

She's not a 70s-era housewife with a secret life of pills and porn.

She's not Antonia with a Pearl Earring.

And I may know little about Nebraska, but I'm pretty sure it's not amber waves of freakin' bamboo that grow there.

2

2

Such a long journey ... well worth taking

(read a different edition)

A better understanding of the political events occurring in the background would have enriched my reading of this, but even without, Mistry was able to catch and hold my attention, weaving layers of story and symbolism together, creating a sometimes farcical, bittersweet domestic tale.

I felt like I got to know this group of (self-declared) middle-class Indians and their microcosm of that larger world a little bit better. I certainly got to smell it - from frangipani and sandalwood to rotting garbage and gutters full of sewage.

Mistry is such a sensual writer - he really has the capacity to bring you right into the world of his novels with these amazing details, characterizations and juxtapositions: superstition with philosophy, cruelty with kindness, great beauty with great ugliness. And his characters are so alive, so large, containing multitudes, as Whitman would say.

Really lovely and awful and fantastic and real - all at once.

3

3

Let us go then, you and I ...

The recent facebook 'post a poem and get a poet' meme showed a dearth of poetic sensibility on my feed, but what it did do (thank you Ceridwen!) was get me to go back and read again TS Eliot's The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock.

And then stumble across various readings, including Eliot's own, linked in the title, and also:

and, oh kill me now, who is this VERY famous actor?

I like Eliot's own best; followed by Hopkins', which at first I thought too rushed but after a couple of listens, like his modulation of timing and emphasis.

Maddaddam: Glimmers of antidiluvian grief and hope

It is too soon to rate - although I've picked 4.5 for now. The trilogy overall, though, is an absolute five. A stunning vision; exceptional execution; provocative themes about greed and ethics, environmental degradation, out-of-control technology ... and maybe a shred of optimism for humanity, such as it is or will be. (I'm hoping that someone is working on the Crakers in a lab somewhere.) An upvote for resilience and hope, at least in the short term.

I know most people thought the previous two, Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood - the latter in particular - stronger, but I don't know: this one grabbed me and really packed an emotional punch. I think, perhaps, it was the innocence-versus-corruption theme throughout that captured my heart. Also, the theme and structural reinforcement of the drive for story-telling and mythmaking: the critical importance that telling our stories, documenting them, passing them on, which is all we have to (re)create meaning and provide comfort in a world that is otherwise dark and empty. "People need such stories, Pilar said once, because however dark, a darkness with voices in it is better than a silent void."

Being the last in the trilogy, and the one that brings it all together, MaddAddam also gets high marks for the resolution: a strange mix of resigned sadness, more like grief, and hope.

(show spoiler)

The idea that we are oil-barrelling blindly down a road towards this--and that it is too late to stop or even swerve--is fundamental here, as in the earlier two. The details are so specific and so current (e.g., fracking in northern Alberta and pipelines in the Arctic) we cannot fail to recognize them. Atwood's postscript emphasizing that everything she describes is part of today's technology or at the least theoretically possible is chilling.

She doesn't need to tell us that - the sense of familiarity and of the inevitable, looming plausibility of it all is visceral.

Atwood leaves us here at the end of this trilogy with enough ambiguity and open-endedness that some interpretation is still required; enough to prevent our complacency, perhaps. There may be no hope that we can prevent our fall, but overall, the pigoons and the Crakers and the stories being passed on is maybe enough for our regeneration.

(show spoiler)

(show spoiler)

(show spoiler)

(show spoiler)

Thank you. Good night.

4

4

Reading progress update: I've read 289 out of 416 pages.

Engrossing and brilliant in a dozen different ways, not least of all for the multiple ways of story-telling, and how/why they are important. Writing and mythmaking as a way to recreate meaning in the world.

p. 154:

p. 257:

I am not in this part of the story; it hasn't come to the part with me. But I'm waiting, far off in the future. I'm waiting for the story of Zeb to join up with mine. The story of Toby. The story I am in right now, with you.”

1

1

A Brontë Brain on a Page

This novel is such an accomplishment. Emily Brontë, you ROCK.

I say this, even though page for page, my heart and soul belongs with Charlotte – and specifically, with Jane Eyre and Villette. It’s just more of a match for me and who I am.

Yet I admire and am astounded by Emily’s talent. That admiration comes from now knowing the broader context of her life. I certainly didn’t feel it the first time through WH – when I dismissed the achievement because of the over-the-top plotting and characterization. It just seemed so far-fetched way back when; just not my thing.

Yet on re-reading, I was unable to distance myself from the characters, as extreme as they are. I don’t see them, now, as unrealistic - in fact, they were all too real. I felt a powerful revulsion for them and especially, for the child abuse. Meaning, I felt both repulsed by their bad behaviour and also sympathetic for the abuse they experienced that made that behaviour all the more likely, and all the more tragic.

I literally had spasms of anger course through me towards the end. On many occasions, I contemplated whether to stop reading - I found it so painful.

There's a nature/nurture theme here that I don't think Emily got quite right. She did not differentiate well enough the different nature/nurture scenarios and their effects on character. Basically, all the nasty pieces of work were nasty in the same ways, despite various combinations of inborn temperament and parenting/environment.

But even to tackle it (a woman who had about three years of formal schooling and had travelled just barely more than the younger Cathy had by age 13) is such an impressive feat.

And even if you peel away that (unnecessary?) thematic layer, the drama of the story and characters stand. The miracle of a woman like Emily Brontë creating this thing that is 100% a product of her own imagination stands.

As she herself says, through her housekeeper/storyteller (and how clever is THAT!):

“I certainly esteem myself a steady, reasonable kind of body … not exactly from living among the hills, and seeing one set of faces, and one series of actions, from year's end to year's end: but I have undergone sharp discipline which has taught me wisdom; and then, I have read more than you would fancy …”.

Virginia Woolf, in A Room Of Ones Own, questioned why the Brontës – and Eliot and Austen, too – wrote novels. Why the novel? She saw Emily, had she lived or lived in different times, as a dramatic playwright: as potentially transcendent as Shakespeare.

So do I.

I am still beyond pissed at Charlotte for destroying Emily’s second novel after her death. (I love you, Charlotte; it’s your behaviour I dislike). And (or so), I haven’t yet read her forward to the second edition of WH published after Emily’s death, included in my Oxford World Classics copy, along with a selection of Emily’s poems and some reasonably competent end notes.

Juliet Barker’s assumption is that Charlotte ultimately deemed Emily’s second novel inappropriate for what novels should be – which, Charlotte believed, was what would be marketable and what would preserve and protect the integrity and reputation of the sisters.

But Emily didn’t give a fig about what the neighbours – or the public at large – thought.

She had access to the richest, most colourful, most interesting, most stimulating world close at hand, not within or close by the four walls of the Haworth Parsonage, but within her own imagination. Nothing else was relevant to her.

She didn’t need the society of others (but for her siblings and her beloved dog, Keeper); she didn’t need instruction or exposure to ideas beyond the large library she had at hand. She had an ever-expanding world within her own brain, with none of the limits imposed by mid-19th century Yorkshire or what anyone thought of her or her writing.

Wuthering Heights is a matured version of the juvenilia – specifically, the Gondal world where Emily’s imagination, her life and her soul, lived. Enter it with her: whether you like that world or not; whether you are drawn to it or want to revisit it; whether you respond to its characters or its themes is irrelevant, she will make you feel it .

Wuthering Heights is Emily’s brain on a page. She didn’t create a world and send it out to the reader through the mundane conduit of publication, as much as she opened a door to her soul and invited the reader in.

That said, she did write and publish it, pouring out her thoughts – strange and dark and disconnected (but not really) from the outside world; an alternate universe, but a universal and lasting legacy in a novel – her only one – and one that remains in print and among the very best of a century of best novels.

Transcendent. Shakespearean. Emily Brontë.

Believe it.

Wuthering Heights - reading progress update 129/341 pp.

Whoa. Some crazy-ass shit going on here.

Honestly, it's so over-the-top, I'm starting to find it funny. Gotta admire the ironic undertone throughout, too ... was Emily's tongue planted firmly in cheek for much of this?

Emily, Emily, Emily ... what must it have been like in your brain?

<<< wanna see THIS movie version (why does Laurence Olivier look like Frankenstein?)

1

1

Perfect follow-up to Barker's Brontë bio

Woolf's genius insights into 19th C women writers - C & E Brontë, Austen, G Eliot - in chapter four of A Room of One's Own takes one of the central themes explored in Barker's biography to the next level: the struggle for poor (i.e., all) women to make a living by their pen, to write in their own voice and resist the dismissiveness or worse, hostility, of the patriarchy.

"...what had George Eliot in common with Emily Brontë? Did not Charlotte Brontë fail entirely to understand Jane Austen? Save for the possibly relevant fact that not one of them had a child, four more incongruous characters could not have met together in a room ..."

[after an extensive quote from Jane Eyre] "... the woman who wrote those pages had more genius in her than Jane Austen; but if one reads them over and marks that jerk in them, that indignation, one sees that she will never get her genius expressed whole and entire. Her books will be deformed and twisted. She will write in a rage where she should write calmly. She will write foolishly where she should write wisely. She will write of herself where she should write of her characters."

[of C Brontë] "She knew, no one better, how enormously her genius would have profited if it had not spent itself in solitary visions over distance fields; if experience and intercourse and travel had been granted her."

[continuing] "...we must accept that fact that all those good novels, Villette, Emma, Wuthering Heights, Middlemarch, were written by women without more experience of life than could enter the house of a respectable clergyman; written too in the common sitting-room of that respectable house and by women so poor that they could not afford to buy more than a few quires of paper at a time upon which to write."

"The portrait of Rochester is drawn in the dark. We feel the influence of fear in it; just as we constantly feel an acidity which is the result of oppression, a buried suffering smouldering beneath her passion, a rancour which contracts those books, splendid as they are, with a spasm of pain." [what Woolf calls 'acidity' is markedly different, I think, than the widespread accusations of coarseness levelled by contemporary male reviewers, predominantly, at Jane Eyre, and both Emily's and Anne's novels too].

And here's the bit that had me leaping off the sofa and typing to you now:

"What genius, what integrity it must have required in face of all that criticism, in the midst of that purely patriarchal society, to hold fast to the thing as they saw it without shrinking. Only Jane Austen did it and Emily Brontë. It is another feather, perhaps the finest, in their caps. They wrote as women write, not as men write. ...they alone entirely ignored the perpetual admonitions of the eternal pedagogue -- write this, think that. ...Charlotte Brontë, with all her splendid gift for prose, stumbled and fell with that clumsy weapon [the 'male' sentence] in her hands. George Eliot committed atrocities with it that beggar description."

Preach it, Ginny.

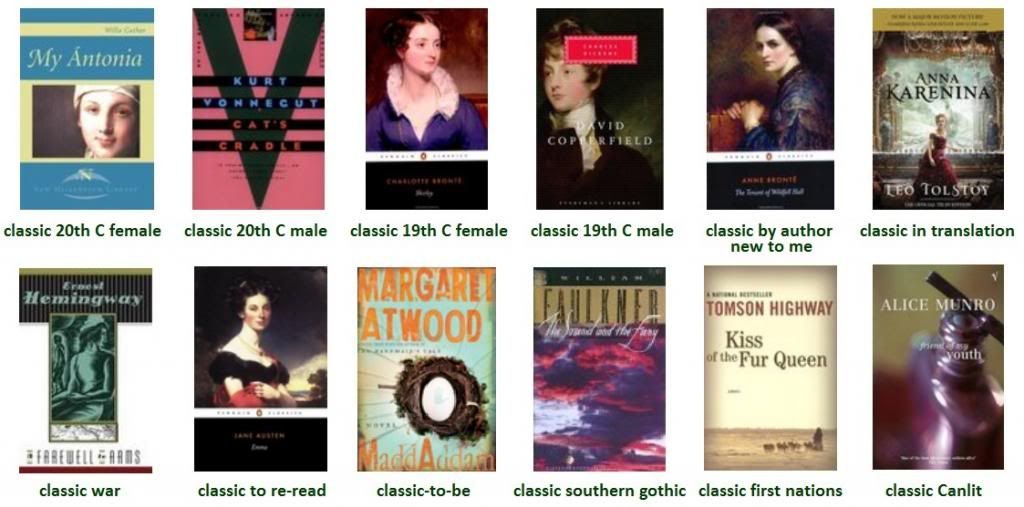

2014 Reading Challenge: Year of the Classics!

I’ve been participating in the GR Challenge since its inception year, 2011, and have been publishing my own Year In Review since 2010. These are opportunities to structure and analyze my own reading in a way that makes the most of the too-little time I have to read and allows me to select the books that have the greatest likelihood of adding value to my reading experience.

While my Years In Review have always included reading commitments for the upcoming year, it wasn’t until last year that I brought the two - the Challenge and the YIR - together, committing not just to a specific number of books but also a specific set (or sub-set, as it turns out), organized around a central idea that emerged from my analysis of the year previous.

This at once brought a deeper level of structure to my reading plan and also took the “quantity” bias out of the Challenge, which was starting to be a drag.

My GR Challenge 2013 was to read to 12 honkin’ big classics, defined as:

1) at least 500 pages long

2) exemplars of the author’s work.

This year, I stumbled across a Classics Reading Challenge here on booklikes (and apologies to the originator, whose name has now been lost to me in the flotsam and jetsam of the feed here), and decided to model my 2014 GR Challenge along similar lines with my own twists.

I wanted 12 books – one per month – and I wanted to maintain gender parity. I also wanted to leave room for other books, so my GR Challenge is set at 48 which will include the 12 classics.

I will be reading these books:

If any of you would like to join me in participating in this Classics Challenge, feel free to drop a note here and identify your own lists – I would love to see them and also hear about your responses to them and to mine.

Happy reading to all in 2014!

Reading progress update: I've read 708 out of 1184 pages (61%)

Tragedy strikes. Branwell, Emily and Anne all die within 9 mos. of each other. So sad. This is making me want to read all of their books, all at once in a great, orgastic Brontathon.

For all the Brontophiles out there, I do have a question for you: What are the two or three strongly-held beliefs you have about the Brontës and their lives, based on "common knowledge"?

E.g., what do you believe about their father, Patrick? About their brother, Branwell? About each sister's personality? About the sisters' relationships with each other?

I ask because, this is the only biography I've ever read of the Brontës so I don't know where Barker is overturning commonly-held beliefs and where she's shoring up existing knowledge.

I am finding Barker's style, which is original-source, evidence-based, very compelling in that she does not hesitate for a second to call out previous biographers - esp. Gaskell - for their incorrect assumptions or interpretations. Yet at the same time, I feel she's drawing her own conclusions too - sometimes, she almost seems to be 'proving the null hypothesis' - where she can find no evidence to support a conclusion, she'll say, it must not have happened; or it must not have happened that way. This may be totally valid. Or it may be her own bias coming out. Her agenda may be one of repairing the reputations - esp. of Patrick and Charlotte.

She glosses over some stuff that seems to need more explanation. In particular, what happened in the years leading up to Branwell's death that turned Charlotte from his closest ally and literary partner to someone who seems cold and compassionless until she totally LOSES it upon his death and finally grants him a morsel of sisterly understanding?

Barker seems intent on showing Charlotte's support for Emily's talent and writing (she acknowledges that C dismisses Anne's work pretty much out-of-hand). She talks about how Charlotte was the driving force behind the sisters being published in the first place; she documents how Charlotte tried to get Anne and Emily to move to her publisher when their own was not publishing WH and AG quickly enough, nor paying them enough. She shows the extraordinary lengths Charlotte went to to honour Emily's desire for anonymity. She positions Charlotte's prefaces to the two sisters' works after their deaths not as undermining their value (as others seem to believe? As an indication of C's professional jealousy toward her other sisses, esp. E?), but as a way to protect and defend their reputations against the harsh criticisms levelled at both. She positions Charlotte as their literary advocate, in other words.

Barker only grudgingly acknowledges that it seems pretty clear that Charlotte destroyed Emily's second novel after her death. Barker concludes that it is likely that Charlotte did not believe the subject matter / topic of Emily's second book would reflect well on Emily's overall legacy/talent. I dunno if I buy that and ...

OMG THERE WAS A SECOND EMILY BRONTË BOOK AND IT'S LOST FOREVERRRRRRRRRRRRRR.

And ...

OMG CHARLOTTE DESTROYED IT!!!! Is that colossal arrogance or just a really crazy grief response? Some combination of the two? Something else?

Reading progress update: I've read 461 out of 1184 pages (40%)

As they enter early adulthood, none of the Bronte children can hold a job exc. Anne, who just puts her head down and makes the best of it. I'm really starting to love her and can't wait to read her books.

Charlotte is constitutionally unable to be a governess. She *really* dislikes children. Mostly, I think she just has a rock-bottom low threshold for anyone or anything that doesn't provide her with the intellectual stimulation she seeks/needs. She's haughty, and arrogant, but also brilliant and clear-sighted about what she wants and who she is.

Emily is flighty and eccentric, even at the young age of 23. But it's clear *she's actually the better writer.* (Although difficult to judge as apples and oranges, right?) She is deeply connected to the natural world and, she loves dogs (and all animals). Her inspiration and art flow from there. She is not oriented to people at all (she is different from Charlotte, who loves people, loves to observe and analyze them, wants to be liked by them, but is socially inept. Emily is also socially inept, most likely, but doesn't give two figs. I love her.).

Branwell is a tragedy looking for a place to happen. His dissolution, according to Barker (who really does have an amazing tendency to mnimize), is less about debauchery than youthful absent-mindedness.

They all seem to have inherited some fatal flaws from their father, mostly a really HUGE disconnect from reality.

OTOH, they all - esp. the girls - are in a truly awful position - neither rich, nor poor, their choices are all the more limited.

The poverty and sickness, even in a relatively good social position, is astonishing. They are dropping like flies. Description of sanitation in Haworth and elsewhere is very telling.

If these sons/daughters of a relatively well-off parson have it this bad,can you just IMAGINE the rest of the lot? :-(

This is REALLY good. It reads fast, and like a novel.

2

2

Reading progress update: I've read 294 out of 1184 pages (25%)

01/02 - page 15 (1%)

To get a BA from Cambridge in 1805, after 4 yrs of study you were given a question in mathematics, moral philosophy, or classical literature & two weeks to prepare & defend a dissertation *IN LATIN*. 3 of your classmates attacked your argument, also orally in Latin, by proposing alternates "in syllogistic form". You returned the favour for them (your performance as defender and interrogator both counted toward the granting of your degree). For an Hrs. degree, you then wrote an exam. Whoa.

01/02 - page 87 (7%)

Gosh, I think she just used "beg the question" incorrectly. And innovatory? Must be a Britishism for innovative. She sure is bound, bent and determined to rehabilitate Patrick Bronte's bad rep. I love her undisguised scorn for previous biographers in the text and endnotes, esp. Mrs. Gaskell.

01/03 - page 165 (14%)

Elizabeth's and Maria's deaths at boarding school (aka 'Lowood' in JE); CB comes home very ill. Barker repeatedly rationalizes that it was "no worse than others" but 12+ deaths in about 4 yrs with 31 girls (1/3 of popn) pulled coz of illness in first 2 yrs? Compared to 11 deaths over 10 yrs at what she says is a comparable boy's school (she doesn't tell us what total popn. of latter is either). She's understating it quant and qualitatively. Why?

01/04 - page 238 (19%)

Lots of focus on the juvenalia, and esp. on Branwell's part. Barker works hard to make this [the intense time/effort the four children put into the creation of these imaginary worlds) seem less extreme, less precocious, less ... weird. I don't buy it. They are all essentially dysfunctional and very unhappy outside of this really closed, really tightknit, fabricated universe of their own creation and the confines of the Haworth parsonage.

01/04 - page 245 (20%)

I'ma need her to stop using the word 'extant'.

01/04 - page 294 (25%)

I hope I don't start to dislike Charlotte so much that it influences my reading of her books. :-( Her talent is immense, but she's coming across as arrogant, judgmental and spoilt. OTOH, Barker is so damn intent on repairing P. Bronte's rep, but he's coming across as naive, rigid, and also scatterbrained. They all seem exceedingly odd, except, so far, Anne.

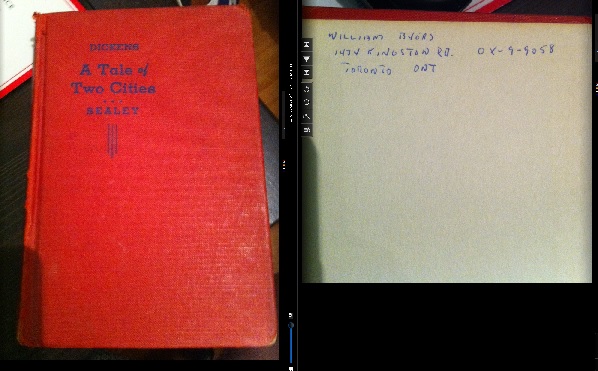

A Tale of Love & Family

This review is dedicated to my Uncle Bill, whose 1935 Copp Clark Publishers' hard-cover I found and began to read just a few days after he died on October 29 of this year.

My family - my parents and their siblings - grew up very poor during and after The Great Depression in Toronto. No one was able to stay in school very long, much less pursue higher education: like Dickens, they were out to work as quickly as they could to put food on the table. Maybe not boot-blacking, but my father left school at 14 and became a mechanic's apprentice, which was surely the 1930s equivalent.

Uncle Bill - as the youngest of all the sibs on both sides (and the last surviving relative of that generation until his death in late October this year) - was able to return to school much later and take correspondence courses at McMaster University; a school I would later attend to do a degree in English literature. So we had that in common, among much else. I don't know for sure that he studied A Tale of Two Cities at McMaster - this book could well date from his high school days - but I do know that his copy of this book sat on my parents' bookcase throughout my childhood and early adult years, after he emigrated to the U.S. And, in the past 15 years, has sat on my own shelf.

So well do I remember it, that I thought it was my father's, and it wasn't until I was inspired to re-read it based on seeing friends' reviews here and on goodreads, that I picked it up and saw Uncle Bill's signature in the front.

So well do I remember it, that I thought it was my father's, and it wasn't until I was inspired to re-read it based on seeing friends' reviews here and on goodreads, that I picked it up and saw Uncle Bill's signature in the front.

The book will now be making its way back to my Aunt Jean, his wife, and my cousin Billy - who bears his name (much like Lucie's son would later bear Sydney's name in honour and remembrance), along with a letter of fond memories and this review. I hope it comes to be read by them or my cousin's children, and treasured for as many years as it's been in our family.

This book is a testament to family ... to friendship, to loyalty, and to love.

And above all else, A Tale of Two Cities is a love story.

It is Dickens at his most florid and most rhetorical, his most humane, his most [melo]dramatic; yet in many ways, his most precise. I vacillate between this and Bleak House as my favourites of his. I would tell you, if you've not read Dickens, to start here. This is as seminal a work in English literature as King Lear or perhaps a more apt comparison, Romeo and Juliet.

For this is a love story.

The last three chapters are intense and so evocative they take my breath away. Beyond the suspense and drama (I'm so glad I have such a bad memory - I only vaguely remembered the book, so was able to enjoy the unfolding of the story despite knowing the general gist of the outcome), they show Dickens as the consummate story-teller that he is, and a masterful rhetorician: the stand-off between Miss Pross and Mme. Defarge is absolutely stunning in its telling and as it reveals Dickens' choices about how to tell an important part of the end - how to bring to completion the themes of loyalty, friendship and love; the positive and life-giving power of allegiance to an ideal as opposed to the destructive and death-inducing allegiance to ideology.

"[Mme. Defarge] knew full well that Miss Pross was the family's devoted friend; Miss Pross knew full well that Madame Defarge was the family's malevolent enemy.

It was in vain for Madame Defarge to struggle and to strike; Miss Pross, with the vigorous tenacity of love, always so much stronger than hate, clasped her tight, and even lifted her from the floor in the struggle that they had."

(my underline - I just love that phrase: "the vigorous tenacity of love")

There is something, even, of Paradise Lost here. There is something on that grand a scale in depicting the fight between good and evil. Among so many dualities, set up from that absolutely extraordinary beginning paragraph that many of us can quote by heart and the title itself, good and evil/love and hate/life and death is what this book comes down to.

There is also an acknowledgement of the grey area between the polarities. There is an understanding that evil people are doing evil acts, but that these are fomented within a social and historical context: "Crush humanity out of shape once more, under similar hammers, and it will twist itself into the same tortured forms. Sow the same seeds of rapacious licence and oppression over again, and it will surely yield the same fruit according to its kind."

It's very big: thematically, historically. And yet it's also very (for Dickens) concise. That combination is extremely potent, and probably the central reason I love it so much.

Something else to be said is the relative absence of humour or caricature as is common in Dickens, with the exception of Jerry Cruncher. Dickens - with, again, that precision - uses Jerry throughout the novel as a character that unites and advances the plot in specific ways at specific points; but he also allows him to evolve and grow in a way that he doesn't always, even in Bleak House.

I notice this time 'round that Dickens has the jaw-dropping audacity to insert what is, I believe, the only sustained comical scene in the novel (Pross and Jerry trying to make a plan; Jerry's "wows") right before its most tragic. And it IS funny, and a few pages later those tears of laughter turn to tears of anguish. This is incredible writing.

The dualities in A Tale of Two Cities could be the focus of an entire review, but the duality alluded to in the title - the two cities, at two different times - allows Dickens to make a separate, more practical and equally important point. The Dickensian point. (As an aside, the cities, the years - places, times, inanimate objects (Sainte Guillotine) are personified; occupations (knitting, shoe-making, wood-cutting, road-mending) take on an importance beyond the pedestrian, become representative in a way that supports its epic feel.)

While Miss Pross represents England and a sense of English superiority, Dickens is not merely dredging up the ages old English-French conflict; he's saying something more subtle: that London at the time he was writing was a hair's breadth away from Paris during The Terror in terms of social inequities. That these conditions, in which human brutality and cruelty arise and dominate - for a time - are predictable, repeatable. That there is a dark side to the coin: the best of times and the worst of times; wisdom and foolishness; hope and despair exist side by side across all times, all places.

The point of Carton's prophetic observations at the end is that this, too, shall pass; that, in the blink of an eye, positions will be switched (view spoiler). Yet as constants, Dickens is also always the optimist: people have the capacity for great good, as well as great evil; retribution and vengeance will be matched and outlasted by generosity and goodness; and love will, in the end, triumph.

For this is, above all else, a love story.

Middles & marriages (p. 181/366) 49%

This is the second book where I've noted that a - perhaps the - critical plot point occurs at exactly the middle of the story. The other was in The Portrait of Lady. And both have to do with a marriage: one might stretch it to say, the joining together of two halves.

I like this. It feels right. And, with Dickens and James, I believe it is entirely intentional.

2

2

Congrats, Lynn Coady!

Lynn Coady wins 2013 Giller Prize for her collection of short stories, Hellgoing.

'tis a good year for short-story writin' Canadian women!

4

4

4

4