Eccentric Musings (jakaEM)

"I have undergone sharp discipline which has taught me wisdom; and then, I have read more than you would fancy." Emily Brontë

still figuring this place out - Jen W

Currently reading

A Tale of Love & Family

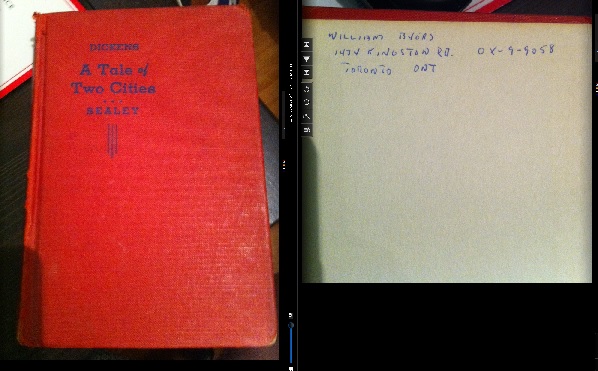

This review is dedicated to my Uncle Bill, whose 1935 Copp Clark Publishers' hard-cover I found and began to read just a few days after he died on October 29 of this year.

My family - my parents and their siblings - grew up very poor during and after The Great Depression in Toronto. No one was able to stay in school very long, much less pursue higher education: like Dickens, they were out to work as quickly as they could to put food on the table. Maybe not boot-blacking, but my father left school at 14 and became a mechanic's apprentice, which was surely the 1930s equivalent.

Uncle Bill - as the youngest of all the sibs on both sides (and the last surviving relative of that generation until his death in late October this year) - was able to return to school much later and take correspondence courses at McMaster University; a school I would later attend to do a degree in English literature. So we had that in common, among much else. I don't know for sure that he studied A Tale of Two Cities at McMaster - this book could well date from his high school days - but I do know that his copy of this book sat on my parents' bookcase throughout my childhood and early adult years, after he emigrated to the U.S. And, in the past 15 years, has sat on my own shelf.

So well do I remember it, that I thought it was my father's, and it wasn't until I was inspired to re-read it based on seeing friends' reviews here and on goodreads, that I picked it up and saw Uncle Bill's signature in the front.

So well do I remember it, that I thought it was my father's, and it wasn't until I was inspired to re-read it based on seeing friends' reviews here and on goodreads, that I picked it up and saw Uncle Bill's signature in the front.

The book will now be making its way back to my Aunt Jean, his wife, and my cousin Billy - who bears his name (much like Lucie's son would later bear Sydney's name in honour and remembrance), along with a letter of fond memories and this review. I hope it comes to be read by them or my cousin's children, and treasured for as many years as it's been in our family.

This book is a testament to family ... to friendship, to loyalty, and to love.

And above all else, A Tale of Two Cities is a love story.

It is Dickens at his most florid and most rhetorical, his most humane, his most [melo]dramatic; yet in many ways, his most precise. I vacillate between this and Bleak House as my favourites of his. I would tell you, if you've not read Dickens, to start here. This is as seminal a work in English literature as King Lear or perhaps a more apt comparison, Romeo and Juliet.

For this is a love story.

The last three chapters are intense and so evocative they take my breath away. Beyond the suspense and drama (I'm so glad I have such a bad memory - I only vaguely remembered the book, so was able to enjoy the unfolding of the story despite knowing the general gist of the outcome), they show Dickens as the consummate story-teller that he is, and a masterful rhetorician: the stand-off between Miss Pross and Mme. Defarge is absolutely stunning in its telling and as it reveals Dickens' choices about how to tell an important part of the end - how to bring to completion the themes of loyalty, friendship and love; the positive and life-giving power of allegiance to an ideal as opposed to the destructive and death-inducing allegiance to ideology.

"[Mme. Defarge] knew full well that Miss Pross was the family's devoted friend; Miss Pross knew full well that Madame Defarge was the family's malevolent enemy.

It was in vain for Madame Defarge to struggle and to strike; Miss Pross, with the vigorous tenacity of love, always so much stronger than hate, clasped her tight, and even lifted her from the floor in the struggle that they had."

(my underline - I just love that phrase: "the vigorous tenacity of love")

There is something, even, of Paradise Lost here. There is something on that grand a scale in depicting the fight between good and evil. Among so many dualities, set up from that absolutely extraordinary beginning paragraph that many of us can quote by heart and the title itself, good and evil/love and hate/life and death is what this book comes down to.

There is also an acknowledgement of the grey area between the polarities. There is an understanding that evil people are doing evil acts, but that these are fomented within a social and historical context: "Crush humanity out of shape once more, under similar hammers, and it will twist itself into the same tortured forms. Sow the same seeds of rapacious licence and oppression over again, and it will surely yield the same fruit according to its kind."

It's very big: thematically, historically. And yet it's also very (for Dickens) concise. That combination is extremely potent, and probably the central reason I love it so much.

Something else to be said is the relative absence of humour or caricature as is common in Dickens, with the exception of Jerry Cruncher. Dickens - with, again, that precision - uses Jerry throughout the novel as a character that unites and advances the plot in specific ways at specific points; but he also allows him to evolve and grow in a way that he doesn't always, even in Bleak House.

I notice this time 'round that Dickens has the jaw-dropping audacity to insert what is, I believe, the only sustained comical scene in the novel (Pross and Jerry trying to make a plan; Jerry's "wows") right before its most tragic. And it IS funny, and a few pages later those tears of laughter turn to tears of anguish. This is incredible writing.

The dualities in A Tale of Two Cities could be the focus of an entire review, but the duality alluded to in the title - the two cities, at two different times - allows Dickens to make a separate, more practical and equally important point. The Dickensian point. (As an aside, the cities, the years - places, times, inanimate objects (Sainte Guillotine) are personified; occupations (knitting, shoe-making, wood-cutting, road-mending) take on an importance beyond the pedestrian, become representative in a way that supports its epic feel.)

While Miss Pross represents England and a sense of English superiority, Dickens is not merely dredging up the ages old English-French conflict; he's saying something more subtle: that London at the time he was writing was a hair's breadth away from Paris during The Terror in terms of social inequities. That these conditions, in which human brutality and cruelty arise and dominate - for a time - are predictable, repeatable. That there is a dark side to the coin: the best of times and the worst of times; wisdom and foolishness; hope and despair exist side by side across all times, all places.

The point of Carton's prophetic observations at the end is that this, too, shall pass; that, in the blink of an eye, positions will be switched (view spoiler). Yet as constants, Dickens is also always the optimist: people have the capacity for great good, as well as great evil; retribution and vengeance will be matched and outlasted by generosity and goodness; and love will, in the end, triumph.

For this is, above all else, a love story.

5

5

2

2